A lot of times math can get pretty dry when it stays only in the theoretical and abstract realm too long. While word problems are the bane of many students, in a lot of ways they can really make some mathematical concepts interesting by bringing some of the abstract down into some pretty useful concrete methods of getting at some useful numbers.

Take this following example:

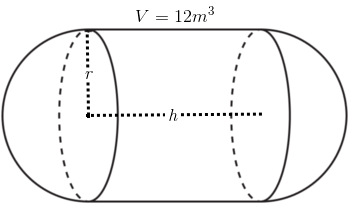

Figure 1

An local steel company has been contracted to build a propane tank as shown in figure 1 that must have an interior volume of $12m^{3}$ However, to save on paint and steel costs, the company wants to know the minimum radius possible such that the surface area of the tank is minimized.

By looking at figure one we can see that the basic shape of our tank here is a cylinder with a hemisphere on each end. Lucky for us this makes getting the formula for the total surface area pretty easy; all we have to do is add the equations for two hemispheres to the equation for a cylinder. Doing so yields:

Which simplifies to:

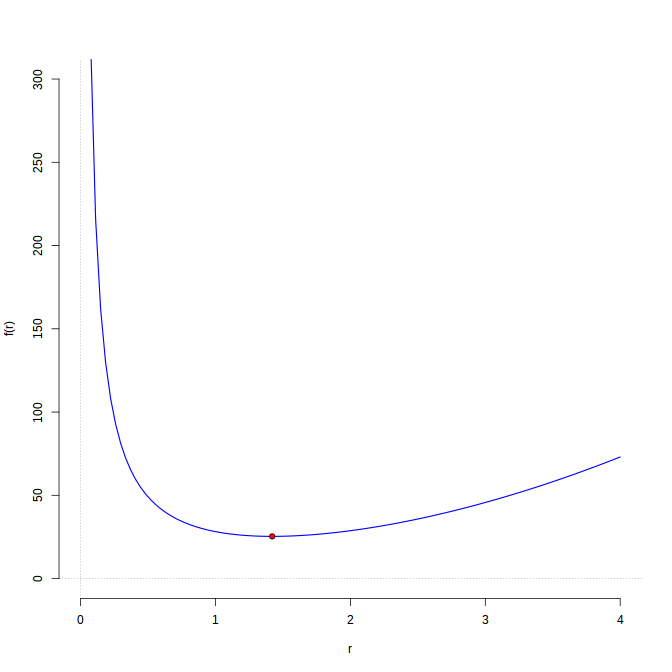

This is the equation we are looking to minimize, specifically for the variable $r$. This is sometimes called the primary equation. To see this graphically:

R code for generating this graph

Some notes on this graph. We can safely ignore all points where $r<0$ because we obviously cannot have a negative radius for our tank; this is why the graph is drawn with both axes at 0 and beyond. Additionally, this isn’t technically the graph for the equation I just created. Instead this is the plot for the same equation but with $h$ solved in terms of $r$, such that there is only one unknown variable. I’ve skipped ahead here a little bit by displaying the graph, but I think it’s valuable to see graphically what we’re working towards and to see the physical point that we’ll be mathematically solving for, so keep that in mind.

The point notated on the graph is the value we’re looking for. This is the function’s local minimum, and represents the spot on the graph where the variable we solved for is at its lowest value. To find the value of this point mathematically, we can employ a little algebra and some calculus. If you notice from our equation for the tank’s surface area, we have two unknown variables, $r$ and $h$. In order to get our value for $r$ we need to employ some way to substitute out $h$ in terms of $r$.

To do this we’ll use a bit of algebra and the fact that we know that the volume of the tank will equal $12m^{3}$. Using the equations for the volume of a sphere and the volume of a cylinder and the fact that our volume will be equal to $12m^{3}$, we can produce the following equation:

This equation is called our secondary equation, or sometimes called our constraint. Since we want to substitute out $h$ in our surface area equation, we can solve for $h$. This yields:

Now that we have an equation for $h$ we can plug this into the $h$ value in our surface area equation and get an equation for the surface area of the tank in terms of $r$:

Simplifying this will yield the following function in terms of $r$:

Now if we take the first derivative of this function we’ll end up with the following:

Now we can put some things we know about graphs and calculus into good use. At any maximum or minimum point we know that the graph will be exactly that: at it’s maximum or minimum value. This means that at these points, the function will have no slope, or a slope of $0$. Since the derivative of a function $f$ computes the slope of $f$, if we set the derivative function we just computed above to $0$, and solve for $r$, we can compute the value of $r$ at which the function is at its minimum. This is why this process is called minimization, or minimizing a function.

Therefore we can take this equation:

and solve for $r$, yielding:

And there we are. We now know that the company should make the radius of the tank approximately $1.42m$ to keep an interior volume of $12m^{3}$ with minimal surface area.

At the end of the day, even this example is a little bit arbitrary but I hope that the somewhat believable application of this kind of math makes it more clear how some of these tools we’re all forced to learn can actually be made useful in real life.